About Government Comics

In 1918, the Bureau of Cartoons was established by the Committee on Public Information as a method for recruiting the nation's cartoonists to promote various campaigns during World War I. The following year, after the war ended, the CPI and its Bureau of Cartoons were abolished, but over the next hundred years the federal government has continued to use cartoons and comics to add visual interest, drama, and fun to the presentation of various types of government information; and to simplify complex concepts for a public diverse in age, learning styles, educational levels, and cultural backgrounds.

Categories

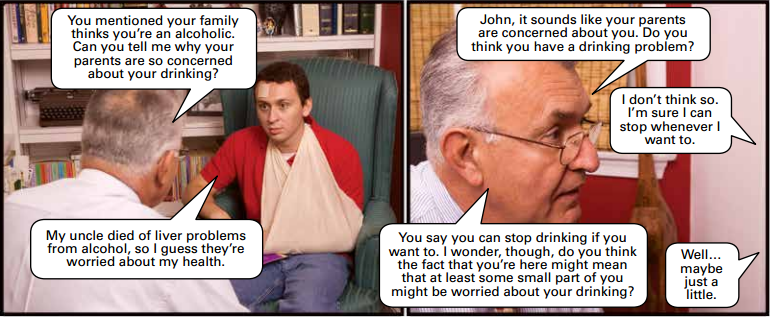

A variety of cartoon formats and genres have been used to illustrate government publications over the decades, ranging from simple illustrations, single-panel or single-page cartoons, or comic strips, to more elaborate storyboards, comic books, fotonovelas, and in more recent years even some edgy, adult-oriented, high-quality graphic novels.

A variety of cartoon formats and genres have been used to illustrate government publications over the decades, ranging from simple illustrations, single-panel or single-page cartoons, or comic strips, to more elaborate storyboards, comic books, fotonovelas, and in more recent years even some edgy, adult-oriented, high-quality graphic novels.

Government comics are available on virtually every topic under the sun. Some of the most popular include military and civil defense; civic engagement and the workings of the government; environmental issues; employment and social security; health and safety; and consumer awareness.

Many government comics are directed toward specific audiences, and in some cases the audience will determine the nature of the nature of the presentation. For instance, in order to raise awareness about scams being reported among the Latino community, the Federal Trade Commission developed a series of informational pamphlets in Spanish and English presented in the format of the fotonovela, a genre popular among Spanish-speaking audiences. The fotonovela format has also been used to present information and advice on health issues of concern to Spanish-speaking immigrants. Some other specialized audiences for government comics include military personnel, parents, Native Americans, and—of course—children and teenagers.

Cartoonists

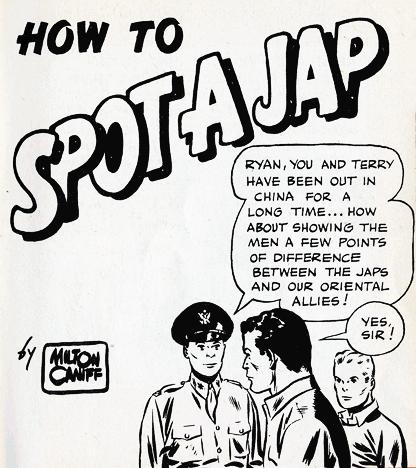

Some of the most famous artists and writers have produced cartoons for government publications, in some cases before becoming a household name. Famous cartoonists who produced government comics while serving in the Armed Forces include George Baker, Will Eisner, Dr. Seuss, Robert Chesley Osborn, and many others. Milton Caniff was found unfit for military service, but still contributed cartoons and illustrations to the war effort. Kurt Schaffenberger served in the U.S. Army during World War II and worked as a translator for the Office of Special Services, but it was later, in the 1960s, when he created The Hidden Crew for the U.S. Air Force.

Some of the most famous artists and writers have produced cartoons for government publications, in some cases before becoming a household name. Famous cartoonists who produced government comics while serving in the Armed Forces include George Baker, Will Eisner, Dr. Seuss, Robert Chesley Osborn, and many others. Milton Caniff was found unfit for military service, but still contributed cartoons and illustrations to the war effort. Kurt Schaffenberger served in the U.S. Army during World War II and worked as a translator for the Office of Special Services, but it was later, in the 1960s, when he created The Hidden Crew for the U.S. Air Force.

Commercially-successful cartoonists who created works for other departments include Charles Schultz, Al Capp, Charles Biro, and Morrie Turner. In some cases, an already commercially published (and copyrighted) cartoon, such as Scott Adams's Dilbert, will be incorporated into a new government document.

Other government cartoons have been produced anonymously, sometimes by professional agencies; sometimes by amateur cartoonists who have more enthusiasm than skill (see for example, the Freddie Food Stamp cartoon below, or the even more primitive Fantastic Tidal Datums).

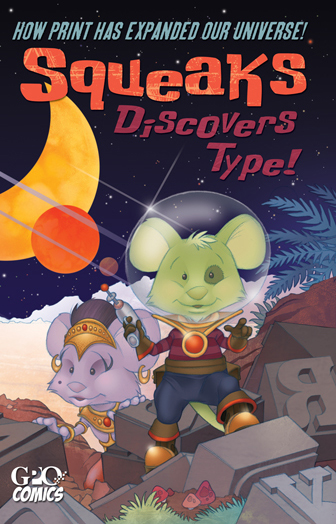

In 2010 the U.S. Government Printing Office released Squeaks Discovers Type!, their first comic book to be produced entirely in-house by GPO employees.

Characters

In other cases unique characters such as Smokey Bear, McGruff the Crime Dog, and Connie Rodd have been created as official mascots representing specific agencies, or messengers promoting specific social agendas.

In other cases unique characters such as Smokey Bear, McGruff the Crime Dog, and Connie Rodd have been created as official mascots representing specific agencies, or messengers promoting specific social agendas.

Many stories in government comics are one-offs, in which a unique character appears only once to explain a specific idea and then is never heard from again. A few of these government characters whose careers never quite took off are Komrad Ivan; El Gato, the Cat; Pip, the Magic Safety Elephant; Sprocket Man; the Garbage Gremlin, Bert the Turtle; and Freddy Food Stamp.

Controversies

Occasionally there have been controversies over using comics to impart government information. These are a few of the objections that have been raised to various government comics over the years:

- They have featured sexist or racist stereotypes, especially those issued during the World War II era. Later comics might contain profane language or violent images unsuitable for children.

- They may trivialize important issues, or oversimplify complex issues. Government pamphlets are intended to make complex ideas easy to understand, but if the explanatory text is minimized to make room for pictures that don't convey a great deal of information, the educational content can end up shortchanged.

- They may promote private businesses at public expense. Although most government publications are in the public domain, in some cases a well-known cartoonist who produces a comic book for the government is under contract to a publisher or syndicate that retains the copyright to the publication, and the characters are sometimes protected trademarks. Some government comics incorporate commercial mascots, such as The Battle of the Energy Drainers, which doubles as a lesson in energy conservation and an ad for Campbell's Soup.

- They waste taxpayer money on frivolous products.

Contexts

In addition to government comics, there are many government documents that are not comics themselves, but comment on various aspects of comics and the comics industry. For example, U.S. Copyright Office Circular 44 provides copyright guidance for cartoonists seeking to protect their intellectual property.

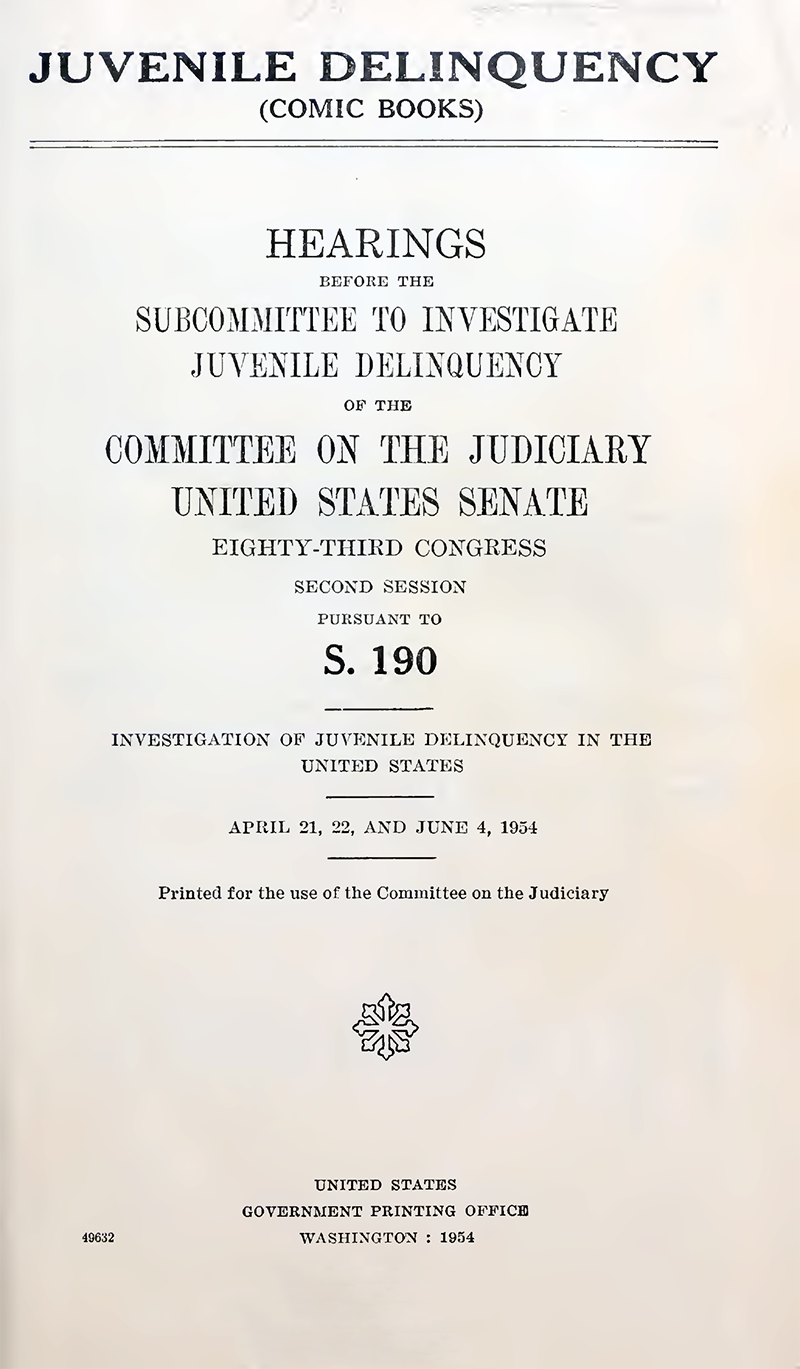

In April and June of 1954, the U.S. Congress held a series of hearings to investigate a possible correlation between crime, horror, and superhero comic books and the current epidemic of juvenile delinquency. One of the key witnesses at the hearings was Dr. Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist who treated juvenile delinquents. He had noticed that many of his young patients read comic books and drew the conclusion that reading comics led to criminal behavior, a thesis that was explored in his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent.

The conclusions and recommendations of the investigating committee were published later in an interim report, but even before this report was released, in order to sidestep the threat of government regulation, members of the comics industry decided to self-regulate by forming the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA). In October of 1954 they adopted the Comics Code Authority, which imposed a code of ethics and standards for comics. Comics that adhered to the code received a seal of approval from the CMAA. Over the years, as comic books competed with television and catered to a more adult audience, publishers chafed at the quaint restrictions of the Comics Code, which seemed a relic of a bygone era. Even though the rules were relaxed in 1971, and again in 1989, they were increasingly ignored by artists and publishers until finally, in 2011, the Comics Code Authority and their code quietly expired.

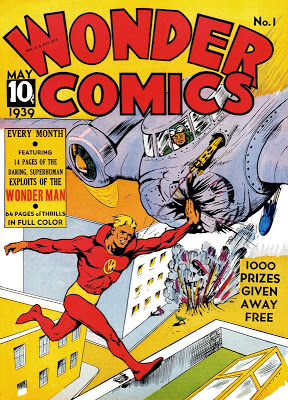

Several court cases over the years have involved comics. One of the earliest was Detective Comics, Inc. v. Bruns Publications, Inc., 111 F. 2d 432 (2d Cir. 1940), in which a judge found that the attributes and antics of a character called Wonder Man were sufficiently similar to those of Superman to constitute a copyright infringement.

If you don't want the copyright to your cartoons or comic strips to be infringed, be sure to read U.S. Copyright Office Circular 44, which provides copyright guidance for cartoonists seeking to protect their intellectual property.

In the late 1980s the Chicago Tribune published a series of Dick Tracy comic strips that told a fictional story involving payola, murder, and a shady concert promotion company called Flipside, Inc. An actual company named Flip Side, Inc. sued the authors and the publisher (unsuccessfully) for libel, invasion of privacy, and emotional distress in the case of Flip Side, Inc. v. Chicago Tribune Co., 206 Ill. App. 3d 641 (1990).

In addition to these works, there are also several government publications that are more tangentially related to comics, such as handbooks on printing, drawing, graphic design, and layout.

Other Resources

Visit the Sycamore Library Service Desk in Sycamore Hall for assistance in locating government document comic books at UNT. You can also contact us by phone (940) 565-2194), or send a request online to govinfo@unt.edu.

These books and Web sites can provide further insight into the world of government comics:

- Government Issue: Comics for the People, 1940s–2000s, by Richard L. Graham

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln's online Government Comics Collection

Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics

, by Carol L. Tilley (in Information and Culture: A Journal of History, Vol. 47, No. 4, 2012).

-

Give Your Outreach Superpowers with Government Comics

This poster presented at the 2019 Federal Depository Library Conference in Arlington, VA explains what government comics are and gives advice for including them in your collection, promoting them to the public, and using them to enhance class assignments and projects. (Note that at the time this poster was presented, Sycamore Library was known as Eagle Commons Library.)

This poster presented at the 2019 Federal Depository Library Conference in Arlington, VA explains what government comics are and gives advice for including them in your collection, promoting them to the public, and using them to enhance class assignments and projects. (Note that at the time this poster was presented, Sycamore Library was known as Eagle Commons Library.) -

UNT Government Comics Flyer

This flyer was created in 2023 to promote the UNT Government Comics subject guide and the Government Comics collection in the UNT Digital Library. It includes a brief description of each and a scannable link to each in the form of a QR code. (Note that at the time this flyer was created, X was still known as Twitter.)

This flyer was created in 2023 to promote the UNT Government Comics subject guide and the Government Comics collection in the UNT Digital Library. It includes a brief description of each and a scannable link to each in the form of a QR code. (Note that at the time this flyer was created, X was still known as Twitter.)